A meal of Heaven & Earth

‘Himmel und Ääd’ is what people call a traditional dish in the flatlands around the lower Rhine river in Germany. The name translates to ‘Heaven and Earth’, referring to the two main ingredients of the dish - the apple and the potato. The farmer reaches skyward to pick an apple from the branches of the tree, and bends earthward to dig a potato out of the soil. As a Rhineland child, when I first encountered the dish, I remember thinking "Am I really eating heaven and earth?"

Apples and potatoes, like most plants, are autotrophs. They perform the minor miracle of creating complex organic compounds (their flesh) out of simple ingredients found on the earth and in the sky: water, sunlight, and carbon dioxide. They make heaven and earth available for consumption. Our human food production depends highly on them, and if they were absent, we couldn’t sustain ourselves as a species. In the future, however, new technologies and radical modes of consumption might emancipate the human species from plant-based food production and remove the weight from their autotrophic shoulders. For this Food-Design and Innovation Pairing I sat down with a food innovation startup CEO and an artist, both working on making heaven and earth edible.

Part One: ‘Eating Heaven’

Pasi Vainikka is CEO and Co-Founder of Solar Foods Ltd., a Finnish company that’s been in the headlines recently due to their use of “NASA technology to manufacture food from thin air”. The first thing Pasi tells me is that the connection to NASA is a red herring. “There are papers published by NASA on similar topics, but the technology we use, is patented and is ours.” By ‘technology’ he means the intricate fermentation process by which Solar Foods produces Solein, a protein-rich, tasteless and odourless white powder. To help me imagine how Solein is made, Pasi describes the production line as a brewery. As in beer brewing, Solar Foods uses microbes to transform one material into another, but instead of barley and hop the raw materials for Solein are air and electricity. “There are ancient microbes out there, from prehistoric times, which are able, similar to plants, to create matter out of pure energy,” Pasi explains to me. “Through modern technology we are reconnecting to archaic terrestrial mechanisms. We use a microbe [of course he can’t say which one] which has naturally evolved to produce protein. We harvest that protein from the microbe and can use it to enrich existing foods with protein content. The production of Solein is 100x more sustainable than meat production and 10x more sustainable than plant production.”

"Despite being a white powder, it does not have the qualities of wheat flour for example."

When I asked if one could subsist on pure Solein alone, Pasi laughed. “It is like with any other food: you would not only eat potatoes or apples. You need a complex diet. Solein offers a possibility to place a sustainable protein on our plate. Solar Foods leaves it open for food manufacturers to investigate how to use this material. Despite being a white powder, it does not have the qualities of wheat flour for example.” Perhaps that’s a call to the food designers out there – to imagine possible future recipes from Solein, a little edible piece of sky that may land on our shelves in the next few years.

Himself, Pasi enjoys to eat the light energy that is put into ‘cutting all the vegetables’ in a fresh salad.

Part Two: ‘Eating Earth’

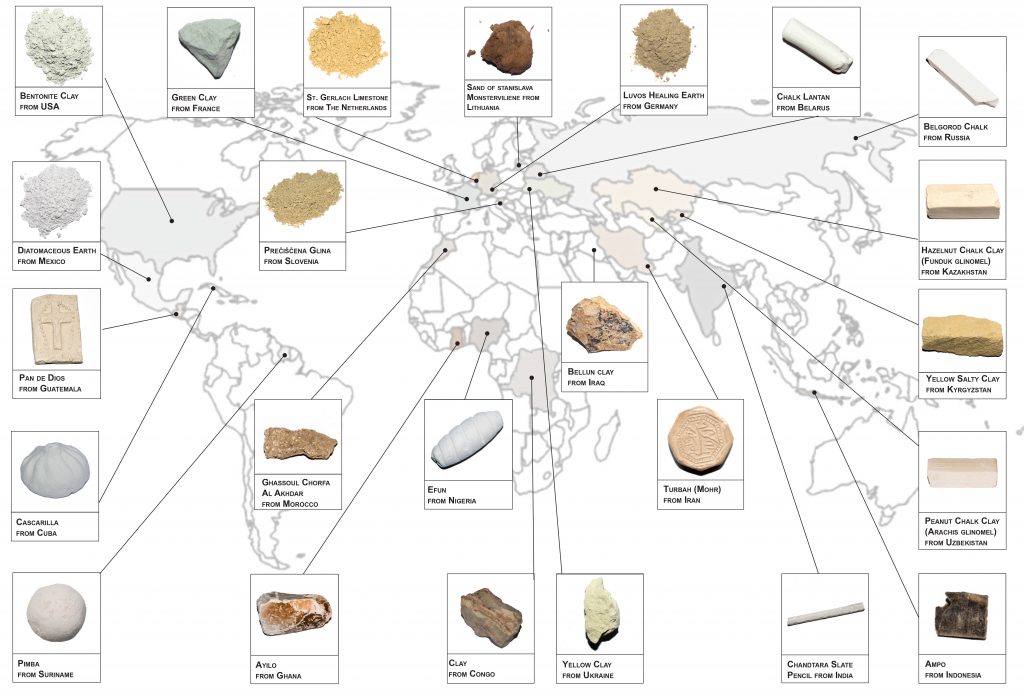

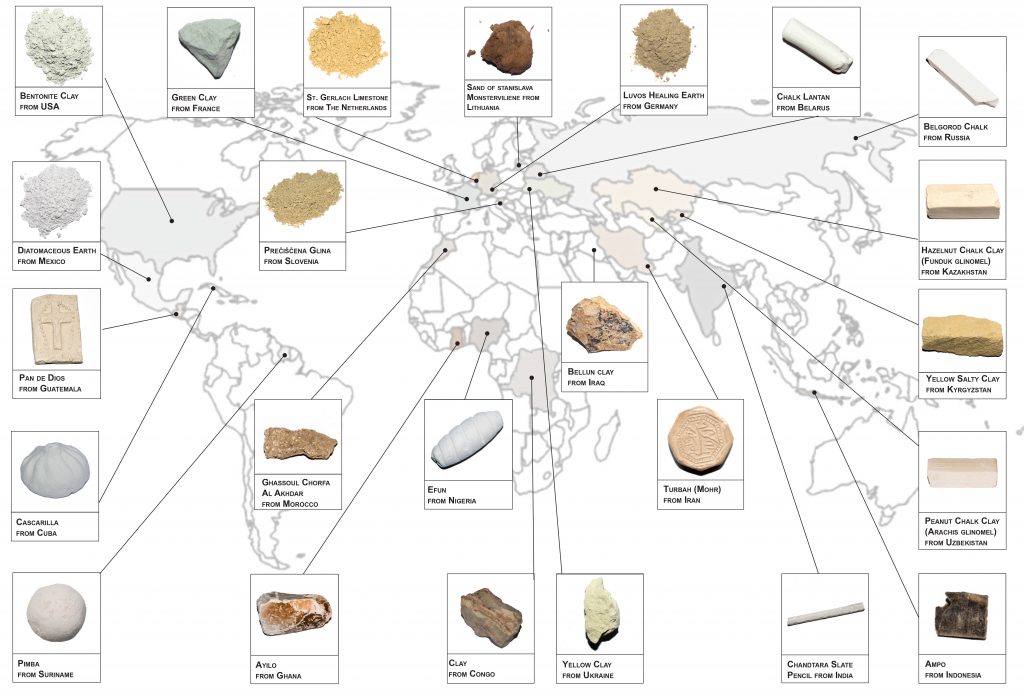

Masha Ru is a Russian artist based in Amsterdam, known for her ‘Museum of Edible Earth’ exhibit at Dutch Design Week (2017). Over the past few years, Masha has been collecting rocks and clays from around the world that have a history of traditional use as food. When I called her up she was in St. Petersburg. She tells me that when she exhibits her work in former Soviet countries, people say that the experience reminds them of ancient practices they’d heard tell of: making love to the Earth before sowing the seeds. ‘Geophagy’, the habit of eating Earth, has been part of many pre-Christian cultures. Evoking cultural memory is an intention that is part of Masha’s exploration of edible earth. I asked her how much soil she eats in a day, and whether she cooks it first. “Not more than 10g usually, but I know people who can eat as much as 2kg of clay a day. However, there is not much cooking with soil I know of, it’s more of an edible artefact.”

I ask if soil is good for increasing minerals in the bloodstream. “There are different opinions in scientific papers regarding geophagy. Earth contains many minerals, but that doesn’t imply they are also accessible to the body. In my work I focus on rocks and clay, so rather inorganic material, no top soil. The tastes can be chalky or muddy, very different in fact.” I tell her she’s a soil sommelier, which makes her laugh. “Sometimes I make field trips to the mountains and try different rocks. But generally I am more interested in traditions, and the social significance of eating earth across the world. Geophagy is generally a taboo nowadays, as a form of ‘Pica’ – a mental condition in which one eats items considered to be inedible.” However, she can imagine the habit of eating soil re-emerging in modern society alongside other eco- and health-driven trends.

Masha’s dietary preference is for grains and vegetables, simple unprocessed foods from the earth. Her work inspires me in its investigation of a culinary domain that is not open to broad public understanding yet, but could bring us closer to crossing a profound border in our eating habits.

What does the disconnection of our food production from the world of plants look like to you?

–

This article is part of ‘Food and Innovation Pairings’, a series of gastronomic matchmakings between players in food innovation technology and visionary artists working around food. The Pairings are initiated by critical food designer Alexandra Genis. Share your thoughts with her at [email protected]